Spartanburg County Man Claims Drug Identification Error Cost His Job

Published: February 15, 2014

By Kim Kimzey GoUpstate.com

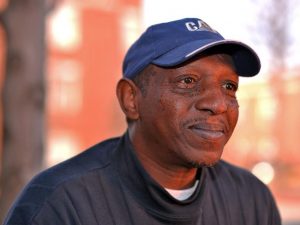

On his drive to work, L. T. passes the Woodruff home he lost.

He sees the flowers he planted in the yard. His family, including his wife of 30 years, made the house a home.

It was one of many things he lost after he was charged with trafficking cocaine.

But it wasn’t cocaine.

L. T., 58, insisted from the moment he was stopped for a traffic violation that the white powder a Spartanburg County sheriff’s deputy found in his 1985 pickup truck was lime.

L. T. said he told others who questioned him that it was lime. He maintained it was lime after a judge set his bond at more than $100,000 — a staggering sum for someone living paycheck to paycheck. Such an amount would be expected for one-and-a-half pounds of cocaine.

According to a sheriff’s office report, the substance tested positive three times for cocaine at the scene. A police dog also “alerted” twice on the bag containing the powder.

But a chemist with the sheriff’s office found no controlled substances when he performed a confirmatory test.

The drug trafficking charge was dismissed the next day — the same day L. T.’s mugshot and the accusation against him were published in the Herald-Journal. News reports alerted worried family members to L. T.’s whereabouts.

In the more than three years since his arrest, L. T. has struggled to find work and rebuild his life. His attorney, Stephen Henry, questions the procedures that resulted in the trafficking charge, while Sheriff Chuck Wright said he doesn’t believe a mistake was made in L. T.’s case and that all procedures were properly followed. Six percent of confirmatory tests in 2013 were negative for illegal or prescription drugs, according to the chemist.

After L. T. didn’t arrive home, his wife and grandson went to the warehouse where he worked and was told he had left early that morning. L. T. said they searched for him on roads to see if he had wrecked. Another relative read about the arrest online.

L. T. said he was unable to call his family or former employer from jail. He said he was told he had to have a card to place a call.

Henry said L. T. was released the next day after the chemist’s test revealed the powder was not cocaine.

L. T. was released on a personal recognizance bond for not using a traffic signal, failure to surrender a suspended tag and driving under suspension. L. T. had been driving with a suspended license and vehicle tag because his car insurance was cancelled due to nonpayment. The bond on the three traffic charges was a little more than $1,100. L. T. could have posted bond and been released that morning, but was unable to post bond for the drug charge, he claimed in a lawsuit against the sheriff’s office.

Henry said because L. T. could not call his employer and did not report to work, he lost his full-time job and main source of income. L. T. said he also lost the health insurance benefits that job provided. L. T. managed to keep a second part-time job.

He still has not found full-time employment, and he lost the pickup truck seized after the traffic stop — he said he could not afford the impound fee.

Henry said the couple has lived on a “financial cliff” since L. T.’s arrest.

L. T. recently settled the lawsuit against the sheriff’s office out of court. He sued for false imprisonment and received $5,000 from the state’s Insurance Reserve Fund.

Wright is unhappy about the settlement. He said Deputy Anthony Hawkins and other officers involved in the case “did exactly what the law requires them to do and our guys did exactly what our policies and procedures said to do.”

L. T. said he was driving home from his late-shift job at a warehouse on July 22, 2010, when a deputy approached him from behind on Highway 221, near the intersection of Highway 215 in Roebuck. It was about 3 a.m.

“I thought he was on call, so I just immediately got over into the other lane, and when I proceeded to get over into the right lane then that’s when he got over…and turned the lights on,” L. T. said.

L. T. said the deputy asked him to step out of his truck and told him he had been stopped for not using a turn signal.

L. T. said he didn’t know at the time that his driver’s license had been suspended. His insurance also had lapsed. L. T., who had recently returned from a trip to Washington, D.C., where he was ordained a church deacon, said he had planned to get insurance that week.

According to the sheriff’s office report, L. T. was arrested for traffic violations. He was handcuffed and placed in the back of a patrol vehicle.

In a deposition taken in February 2013, Hawkins said he and another deputy searched the vehicle and found the white powder.

Hawkins said he used another deputy’s test on the powder. He said all he had was a dropper, and the kit did not have a plastic container to put the substance in, so it was placed on a piece of paper on the hood of a truck. Hawkins said it turned blue — indicating the presence of cocaine.

Hawkins said in his deposition that L. T. first said the powder was bug powder that he got from work, but later said it was lime. That discrepancy was not noted in the report.

Hawkins testified a fourth deputy arrived and field tested the substance a third time. He said the results were positive.

“When they come to the conclusion that it was cocaine, I told them in response, ’That’s lime. That’s not cocaine. You can spread it out there on the ground. I’ll just get some more from my job,” L. T. said.

L. T. — a man who served four years in the Army and looked up to an uncle who had been an officer with the Woodruff Police Department — said he was “hurt” by the accusation. He said he was jailed at about 9 a.m. and was told he had to have a card to make a call.

“They was so bent on me being a distributor, I imagine that’s one of the reasons they didn’t too much care,” L. T. said.

He worried about his wife. L. T. said she had had her second stroke less than a year earlier. She would have expected him home no later than 4 a.m.

L. T. said about 11 a.m., two men in plain clothes questioned him about where he got the substance. He said he told them it was lime and that he had gotten it from his part-time maintenance job because his wife thought she smelled something decaying beneath their house.

Henry said the two officers who questioned L. T. about the supplier were “mystery guys” who have not been identified. “There’s no record of them anywhere in the paperwork,” he said.

L. T. said after family learned he had been arrested, they unsuccessfully tried to raise the money for him to make bond.

Henry said L. T. — who already “was on the edge of his leave time” because he had taken time to care for his wife — could not reach his former employer and was fired.

L. T. said he is not bitter or angry. What hurt the most was losing his main source of income and the ensuing struggle. He did not realize how much had changed in a computer-driven era and said it’s been really hard to find another job. He said some ministers and preachers found it difficult to accept his innocence after the drug charge was dismissed.

Henry said the sheriff’s office needs to review its field drug test procedures and that mistakes were made in L. T.’s case.

“There’s no quality control,” he said.

Henry questioned whether the substances used in the test were outdated. He said Breathalyzers are calibrated and thinks field test kits also should be monitored. He said if officers tested the substance and got a positive result, something is wrong with the test. Henry had an investigator test the same powder with a commercially available kit, and it was negative for cocaine.

Eric Sevigny is an assistant professor at the University of South Carolina whose areas of specialization include drugs and crime.

Sevigny wrote in an email that “field testing is usually done through some (re-agent) test. The officer or drug detection specialist will apply a solution to the substance and interpret the color change as indicative of a general class of substances.”

Sevigny wrote “more sophisticated and reliable technologies” can be used in the field, but are more expensive. Re-agent testing is more common, but it “is subjective and thus potentially inaccurate,” Sevigny wrote.

Sevigny explained a person is asked to “interpret a color response” — determining whether it’s purple, black, blackish-purple — “that can vary by ambient temperature and other conditions. Moreover, there can be adulterants or other drugs that affect the results. Opiates turn one color and cocaine another, for example, but what happens when the substance contains both?”

Sevigny said that after a positive field test, a substance would need to be tested in a lab using “gas chromatography or similar methods in order to stand up in court.”

Gas chromatography was one test used in the confirmatory test of the powder seized from L. T. Lt. Ashley Harris, a chemist with the Spartanburg County Sheriff’s Office, wrote in an email that gas chromatography, coupled with mass spectrometry, is the primary confirmatory test in the department’s forensic lab.

Harris said 6 percent of items analyzed in 2013 were ruled “No Controlled or Prescription Substance(s) Detected.” The figure was 5.2 percent in 2012.

Instruments used in confirmatory tests are “very sensitive” and don’t require a large sample — about 0.01 gram would be enough. If none is left after a presumptive test, Harris said the report would read “No analysis performed.”

Lime would field test positive for cocaine because, Harris wrote, “The presumptive test is nothing more than that…a test that allows you to presume it is positive or negative.”

Harris said a confirmatory test must follow a positive field test to determine whether a substance is a drug. He said the lab doesn’t identify non-controlled substances unless they have a bearing on a case.

Harris said the instrument used to test the powder does not identify lime.

Henry said fortunately, Harris immediately notified others when further testing showed it was not cocaine.

Henry said the amount of lime made L. T.’s a “rare case,” but said it could happen with smaller amounts.

“I don’t think there’s any protection for someone who’s arrested for a drug charge with faulty chemical tests as in this case,” Henry said.

He said the only remedy is to ensure officers have up-to-date tests, follow instructions and use the entire test.

Harris said when the testing solution is made in the lab, it’s tested to show an officer it works when it leaves the lab “and to illustrate how much is needed for a test to be performed. This ‘training’ is required to get a bottle…The officer is instructed that they may bring their bottle in and get a replacement anytime. We also let them know that they can come by and we can test it to show it is working properly anytime they want.”

Asked if he thought the sheriff’s office should review field drug testing procedures in light of L. T.’s arrest, Wright said the agency looks to ensure no errors are made, but said he doesn’t think a mistake was made in L. T.’s case.

“There was a particular reason why that stuff turned up the right color. It might have had a cocaine base in it, but it also might not have been enough of a percentage to charge somebody with. That happens, too,” Wright said.

He questioned where the bag was found and the manner in which the powder was bagged.

According to a sheriff’s office report, Hawkins found a plastic yellow bag “stuffed under the passenger side of the seat. Inside the bag was another brown paper bag with white powder substance inside.”

“I think we just had a bad reading, and I don’t think that’s the officer’s fault. I think that he could only go by what he sees and what he’s trained to do,” Wright said.

Wright praised Deputy Hawkins’ work. He said Hawkins, a Marine Corps veteran who served two tours in Iraq, does a good job of going after dealers and getting drugs off the streets.

Wright said he doesn’t “buy the fact” that the arrest cost L. T. his job and caused other hardships. He said the traffic offenses, including the suspended driver’s license, could be a factor in him not having a job rather than the dismissed cocaine charge.

Wright said jail inmates do not have to have a card to place calls.

“You get a free phone call,” he said.

L. T. said he wanted officers to see that everyone makes mistakes. And he wonders how many other mistakes there have been.

L. T. continues to look for full-time employment. And he holds on to something he did not lose after the arrest — his faith.

“I can only imagine if I didn’t have (God) on my side,” he said before exhaling. “That’s my only strength. He’s my strength.”